Before the winds of change could settle on South Africa’s political landscape in the mid-1990s, the country’s agricultural sector was experiencing its own transformation. In 1996, South Africa welcomed the dawn of agricultural biotechnologies, better known as Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs), with the planting of the first GM maize crop.

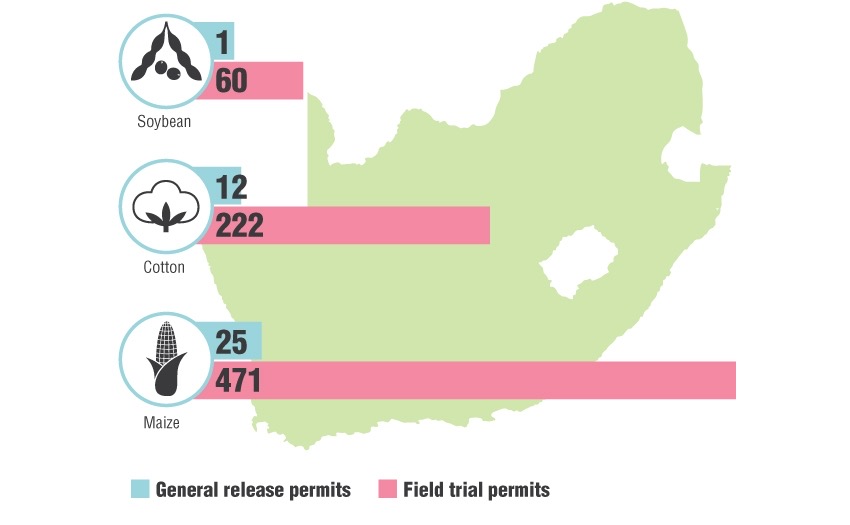

Today, according to a report from the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), the country has a total of at least 2.7 million hectares of land under GM cotton, maize and soybean production, all of which have been approved for general release to the public.

Dr. Hennie Groenewald, the Chief Executive Officer of Biosafety South Africa, a national technology platform which services the country’s biotechnology regulators, researchers, technology developers and the public, says that what Africa’s second largest economy got right from the onset was to develop a robust legal framework to govern the GMOs and GM crops sectors.

“You cannot use GM tech if you do not have the appropriate regulatory framework for it,” said Dr Groenewald in an interview, adding,“This is where the debate usually lies with all the countries that are having discussions [on the GMO legal framework] such as Uganda, and that establishment of a framework is a political process.”

South Africa developed its Genetically Modified Organisms Act 15 of 1997, which regulates all activities related to GMO in the country and has been amended a number of times over the years, shortly after starting the production of GM crops.

The Act aims to provide minimum standards that ensure the food/feed and environmental safety, as well as the socio-economic sustainability of all activities involving GMOs. It regulates research and development, import/export, production, consumption and other uses of GMOs and their products.

South Africa’s GM law also establishes the necessary operational procedures and infrastructure required for the regulation of GMOs. These are responsible for delegating to different state agencies the responsibilities of administration related to the Act, permit condition compliance, evaluation of permit applications and the decision-making process.

“From a South African perspective, the introduction of the few GM crops that we have was a great success if you look at the acceptance from one side and then also look at the impact that they have had,” said Groenewald.

BURKINA FASO

In the West African country of nearly 8,000 kilometres away from South Africa, a bio-safety law was passed in 2006. It paved the way for its farmers to shelve their local cotton in favour of a brand of GM cotton that had been developed by US Company Monsanto, with the approval of Burkinabe authorities.

Between 2008 and 2016, Burkina Faso managed to get 150,000 households to cultivate Monsanto’s cotton gene. However, whatever gains the West African country was making in volumes were not being matched by the quality of the cotton fibre.

Consequently, Burkina Faso made a U-turn, abandoning the cloned cotton, ostensibly until it could resolve the GM cotton fibre quality issue, and returning to the organic cotton through which it had made a name as Africa’s top cotton-growing economy.

UGANDA

In the East African nation of Uganda, on the other hand, the government has so far failed to even take the first step of putting in place the legal regime to govern the research, production and distribution of its GM crops.

Uganda’s Parliament has spent eight years – and hundreds of thousands of dollars – working to pass a law that regulates the development and use of biotechnology. Yet, there is still no end in sight for the proposed legislation that has led to unusually open disagreement between Parliament and the executive arm of the East African nation’s government.

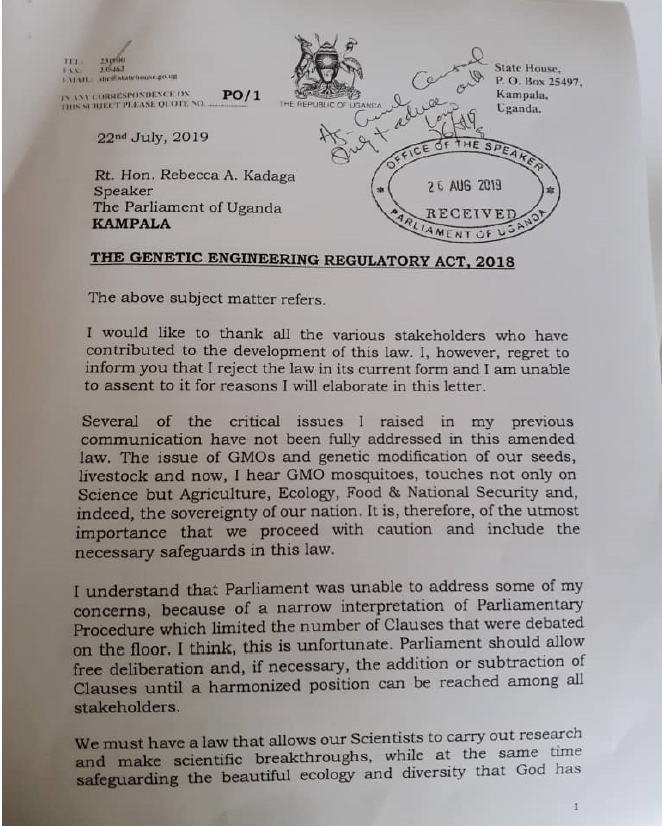

So far, Uganda’s Parliament has signed off the Genetic Engineering Regulatory Bill (initially named the National Biotechnology and Biosafety Bill) not once, but twice – and sent it to the country’s president, Yoweri Museveni, so he could sign it into law. However, the long-serving Ugandan leader has sent the draft law back to the legislative body each time.

In two separate letters to Parliament to notify them of his decision, Museveni noted that aspects of the Bill did not sit well with him and his administration because they could be harmful to the Uganda of tomorrow.

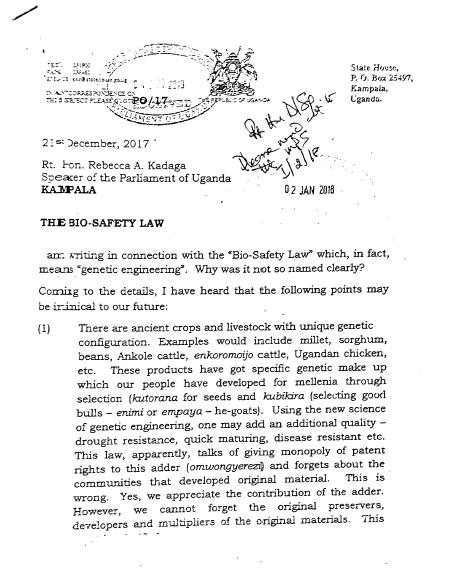

Museveni wrote his two letters, copies of which this publication has obtained, to Uganda’s Parliament within 19 months. In the first letter, dated December 21, 2017, Museveni outlined 11 issues that he said would be “inimical to [Uganda’s] future.” In his second letter, dated July 22, 2019, Museveni concedes that Parliament had made some adjustments to the law but then outlines seven “crucial gaps that remain” unattended to.

“Several of the critical issues I raised in my previous communication have not been fully addressed in this amended law,” Museveni states in his second letter, a four-page memo addressed to the then Speaker of Parliament, Rebecca Kadaga. He then concludes the letter by saying, “I believe that addressing these issues will finally allow us to have a Genetic Engineering Law that is pro-science, pro-people and pro-development.”

So what does South Africa believe it got right that its two sub-Saharan African counterparts didn’t or haven’t yet?

SOUTH AFRICA’S PERSPECTIVE

According to Groenewald, part of the problem, in the case of a nation like Uganda, is the timing. He noted that when South Africa entered into discussions over its GM legislation in the 1990s, the political climate was quite different and the discussions were mostly from a science-based perspective.

“In this [South African] framework we looked specifically at the science and when you come to the risk conclusion that says there is no significant risk, you implement the technology. If you develop those systems in the current environment, there’ll be a lot of political input,” he said. “Uganda, for example, has been debating the issue for many years and they are in a much more difficult position than South Africa [was] in 1997 because back then it was a different environment. We didn’t have all the political influences.”

Today, South Africa is the ninth largest producer of Genetically Modified crops in the world with three commercial crops that have been genetically modified in production mainly for herbicide tolerance and insect resistance. Insect resistant (Bt crops) are those that are able to resist insect damage and herbicide-tolerant crops are tolerant towards glyphosate, a chemical herbicide used to kill both broadleaf plants and grasses.

According to Groenewald, most of the maize sold in South Africa is insect-resistant and herbicide-tolerant.

“We have between 85% – 95% of all the maize in South Africa as GM, 95% – 100% of all the soy is GM and all the cotton in South Africa is GM,” Groenewald said. “This is a reflection that the acceptance is not simply because the people like the technology but because the farmers see the benefits.”

Groenewald admits that there is a small but significant number of people against GMOs in South Africa and accepts that those perceptions also form part of the GMO conversation in the country.

“Depending on where you are and who you are, you’ll have very different reactions to the perceptions towards GMOs,” he said. “But if you want data-based evidence about the introduction and the acceptance of the technology, then you need to speak to the farmers or the users of the traits that are available.”

IN THE FIELDS

A member of our reporting team travelled to Baziya, a town in the Eastern Cape province – one of South Africa’s most rural provinces – to speak to a small scale farmer, Mxolisi Silimela, who has been a maize farmer for more than 10 years and lives off the profits made from his farming activities, which include maize farming.

Silimela currently farms on four hectares of land and produces between 100 and 120 large bags of maize annually, which he sells to local markets and bulk buyers who resell the maize or use it to produce animal feed.

Silimela started using maize seedlings treated with herbicides and pesticides in 2014. Prior to that, he had been using local seedlings as well as organic methods of ploughing, planting and weeding, which were physically demanding and time consuming.

The farming process became much easier for Silimela when he started using Roundup powder, a herbicide which genetically modified crops are designed to tolerate. When farmers spray Roundup powder on their farmlands, it kills weeds but not the maize seedling.

“I started using RoundUp-[resistant] maize seedling in 2014 and it has made life much easier because I don’t spend as much time on the fields as well as money on having to outsource the manpower for weeding and other processes,” he said. “RoundUp maize has been a huge relief for me.”

Although a lot of small-scale farmers like Silimela have embraced the introduction of biotechnologies that have benefited them, it seems that not much has been done to help them understand some negative impacts that these may have. Silimela admitted that although he has had no issues with RoundUp powder as well as RoundUp resistant maize, he does admit that when it was initially introduced to them as farmers, they were not equipped with much information on it.

“We have never really been officially educated on the health impacts of these products we use and anything we know we have researched ourselves or heard through the grapevine,” he said.

GMOs seem to have fared well in South Africa and can be said to be an African success story. However, revelations like that of Silimela from one of Africa’s richest economies –, along with the experiences of Burkina Faso and Uganda — show that there is little room for error in the quest to improve the productivity of Africa’s plants and animals through modifying their genes.