Three journalists from different parts of Africa have over the last few years raked up a series of accolades for their respective works. However, you are unlikely to come across the vast majority of the content that they produce in mainstream, traditional media organisations.

The three journalists, David Hundeyin from Nigeria, Hopewell Rugoho-Chin’ono from Zimbabwe and Rosebell Kagumire from Uganda, are a microcosm of the changing trends in media content production, distribution, and engagement in the digital media age.

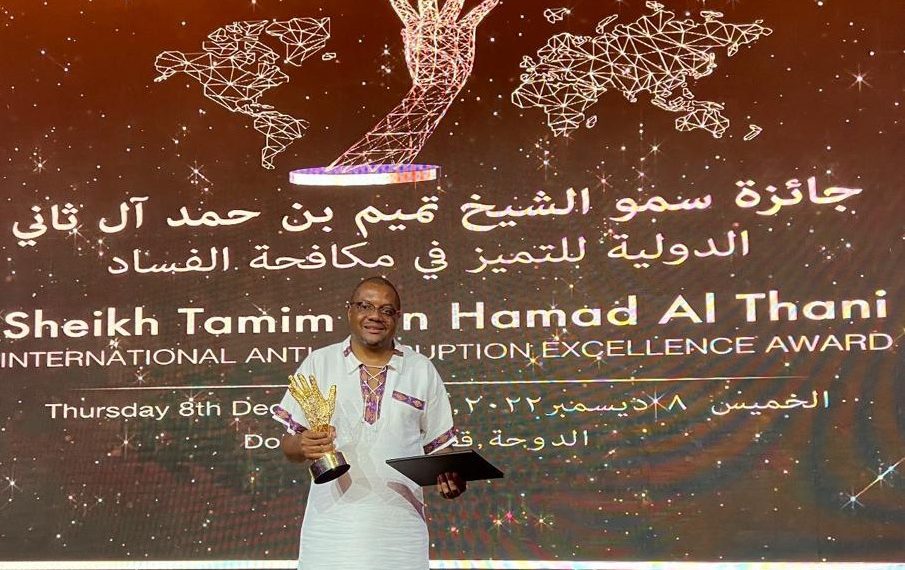

In December, as the eyes of the world, were glued on the FIFA World Cup in Qatar, Chin’ono, 51, was collecting the International Anti-Corruption Excellence Award in Doha for his contribution to the global fight against corruption.

In late October last year, Hundeyin was named the winner of the Distinguished James Currey Fellowship 2023 and residence in Cambridge as an academic visitor at the Centre of African Studies at the University of Cambridge.

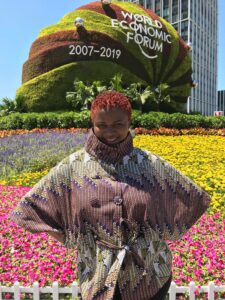

Earlier in the year, Kagumire had been recognised by Avance Media among presidents, UN diplomats, academics and others as one of the 100 influential women in Africa for 2021.

Yet, interestingly, these award-winning journalists with several other reporting accolades to their names have departed from the well-worn path of practicing their craft in newspapers, radio, or television.

Instead, the three have taken a different approach to their journalism. They are leveraging the vast array of resources offered by the new media era, especially the social media age, to produce and propagate their content to audiences in their countries and across the continent.

In 2022 alone, for instance, Hundeyin has published provocative investigative articles on his West Africa Weekly outlet, via substack.com, reports on Nigerian presidential candidate Bola Tinubu, Nigerian’s highest-valued tech start-up Flutterwave, and the BBC’s West Africa operations. All three reports were the subjects of intense social media conversations, often involving weeks of feverish engagement between Hundeyin and the subjects of his controversial stories or their supporters.

Point of departure

In an interview with Jamlab Africa, Hundeyin said his journey towards developing his own publication started because the type of investigative pieces that he preferred to do was making his previous employer a pariah before organisations that offer grant funding to journalism non-profits.

“I could see very clearly that If I wanted to continue doing this kind of work, I need to have an independent platform that is not beholden in any way to the Nigerian CSO (civil society organisation) or NGO (non-governmental organisation) ecosystem or even the Nigerian economy as a whole, I needed to find a new model,” he said.

Eventually, in 2020, Hundeyin zeroed in on Substack, where he registered his West Africa Weekly newsletter. And then life came at him fast! He registered about 3,000 subscribers, fled Nigeria in the aftermath of the #EndSARS Lekki massacre, and then landed on a tweet talking about this programme for Substack writers and journalists called Substack local.

“Substack was trying to do an experiment basically surrounding the creation of local news around the world, so they said they were looking for 12 fellows. I knew it was going to be very competitive, but I applied and ended up being the only person from Africa that was selected. So that obviously put a lot of pressure on me that even though I didn’t necessarily plan to migrate my investigative journalism onto my newsletter, here it is,” he explained.

Buoyed by the funding of US$30,000 that Substack provided to its fellows for 12 months, Hundeyin was able to hire a designer and an editor. In August 2021, Hundeyin was able to do his first investigative long read for West Africa Weekly and the rest, as they say, is history.

For Kagumire, 39, a former print, radio and television journalist in Uganda, the journey to using self-publishing boards was down to the fact that she felt she was outgrowing the traditional media platforms.

“Earlier on in my career, it was very evident that the media format that was pre-existing was not really interesting me enough. It was not enough for me to go and interview people – he said, she said this and that – and there was really little investment in the kind of journalism that I felt was impactful,” she explained.

Kagumire set up one of the first blogs in Uganda, named Rosebell’s Blog, and a YouTube channel where she did journalism that “went beyond interviewing people.” She focused on doing long-form pieces that included her reflections on the issues she was covering.

“I always knew I had something to say, beyond just interviewing people but actually to drive the agenda as a person and understanding and digging deeper into the issues that I wanted to dig into,” she said. “So, the space [in traditional media platforms] was very small and already determined by whoever was in charge, and there was little change. So, for me, it was frustrating [and] it was out of that kind of frustration that I thought, ‘I need to find something that can actually accommodate how I want to communicate and how I want to influence things as a writer.”

Many of Kagumire’s blogs and videos went viral, earning her writing opportunities with outlets such as Global Voices, television commentary slots on global channels such as Al Jazeera and BBC and speaking slots at conferences around the world.

Kagumire’s major areas of focus were pan-African feminism, social justice and socio-political issues which earned her recognition on the global stage as one of the Young Global Leaders under the age of 40 in 2013 by the World Economic Forum, winner of the Anna Guèye 2018 award for her advocacy for digital democracy, justice and equality by Africtivistes (a network of African activists), and winner of Waxal – Blogging Africa Awards, Africa’s first journalist blogging awards, among others. Today, Kagumire is the editor for African Feminism, based in Dakar, Senegal.

Money matters

Kagumire says she had a good six-year stint running her own blogs before African Feminism came calling to return her to a more structured media space set up by like-minded bloggers and activists who sought to have a single online address to undertake their crusading journalism.

Asked about where she was getting the money to sustain her blogging career, Kagumire said she never sought to commercialise the platforms she was using. Instead, she used the platforms as avenues to get the work opportunities that she needed to earn money.

“The platforms were a window for people to know that ‘this is my politics, this is who I am, this is where I communicate.’ They weren’t the place where I was making money, they were connecting me to work opportunities,” explained Kagumire, who took on gigs as a film director, fixer, commentator, writer for mainstream global platforms and a conference speaker.

According to Kagumire, going solo opened her up to opportunities beyond the confines of her home country. In between packaging her blogs, Kagumire did short-term work in South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Senegal, and several other countries around the world.

Hundeyin, on the other hand, intends to commercialise his platforms. So far, his substack platform has 35,377 subscribers, although the number of paying subscribers is still 225. However, he adds that the low number is down more to the payment infrastructure that he currently uses than the willingness to pay for his journalism.

“I have quite a large readership base, it does quite some numbers,” he says, adding, “Part of the problem I had with subscription previously is Substack uses Stripe as its payment process and Stripe only processes payments in US dollars. Nigeria, as you may know, is where the bulk of my readership resides, and Nigeria has a significant capital restriction regime going on. So, basically, you can’t make foreign transactions with your naira card, so a lot of people said they were not able to pay for subscriptions even if they had the money. Last month, I implemented a workaround using a tech platform that made it possible to make payments in naira. Instantly, there was a hundred percent uptake in subscription revenue. So, I am hopeful that this will become the trend.”

Paying the price

Going solo, as the crusading journalists have learned, has its own downside. Without the support of media institutions and networks, journalists often become isolated, and easy targets for attacks by those they report about.

Chin’ono, for instance, has broken stories on his Twitter profile and Facebook pages that have had an impact, including getting a health minister sacked and arrested. However, he’s also become a sitting duck for attacks by Zimbabwe’s political system, including getting arrested at least three times over the last three years.

“The reason why I decided to take up the fight against corruption is that I realised that millions of Zimbabweans are living in abject poverty, and I realised that all those things were being caused by the looting of public funds and the abuse of the natural resources of the country. The fight against corruption can be a lonely battle because sometimes you can be arrested on trumped-up charges and thrown into prison but when I look at what we have achieved, you realise that it is worth it,” Chin’ono said in a video recorded ahead of his anti-corruption award ceremony.

Journalists like Chin’ono, Hundeyin and Kagumire have at times been accused of crossing the journalistic ethical red lines. However, they are non-apologetic about the stance that they take, if it gets the results that they desire to achieve.

Hundeyin says controversial stories will always elicit a response from those who are accused of wrongdoing, so the journalist must be prepared to engage with them and defend the results of his or her investigations, even if it means taking a combative approach at times.

“A lot of people have this weird expectation that when you publish a story, you should somehow pretend as if you have no eyes and ears. You just publish and leave it at that and disappear. I don’t understand how that is supposed to work, especially where often powerful people and institutions are very directly implicated and credibly accused of very serious wrongdoing. Obviously, those individuals or institutions are not going to take it lying down. They are going to start saying that “you are a liar; you are not a good journalist” because that is what they do. So, in that situation, how are you then supposed to sit down and keep quiet? That means that you are agreeing with them,” he reasoned.

For Kagumire, her own crusading work has opened her eyes to the challenges of doing journalism under a model that she believes has some flaws that need to be addressed if it is to have an impact in the digital age.

“This format of journalism that we were sold like you don’t have to have a side is actually a lie. You go to cover stories with a certain [level of] socialisation and a certain understanding, even if it’s a lack of understanding. If you’re a man, you’re arriving to cover a story from a certain position as a man and you have to be aware of that position to challenge yourself to deliver stories that would be different. Unless you’re aware of that, then you’re not going to actually do ground-breaking work for many marginalised people because you don’t see yourself as an important part of the story. So, for me, earlier on, I was like it’s very important to know the things I am working on in-depth,” she said. “So, I felt that stepping out of the newsroom allowed me the kind of interaction [I needed to have] with people whom I could learn from, and that influences how I cover something and how I arrive at certain lenses through which I am covering something. And finding that out early on for me was liberating. I did not have to pretend that I am arriving at this issue without a certain bias.”

Reporting for this story was supported by a micro-grant from Jamlab Africa.

Benon Herbert Oluka is a Ugandan multimedia journalist, a co-founder of The Watchdog, a centre for investigative journalism in his home country, and a member of the African Investigative Publishing Collective.