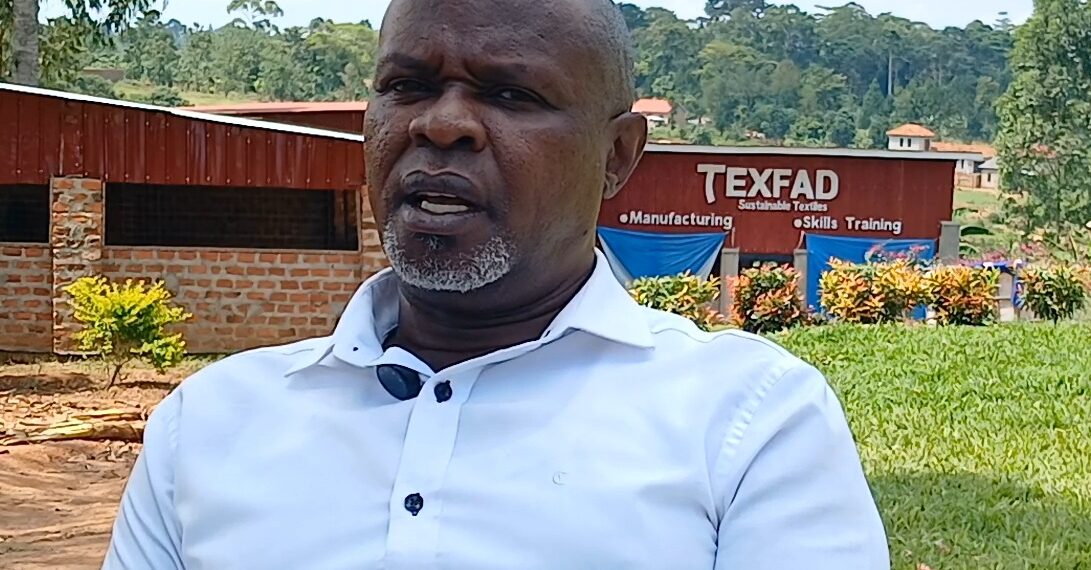

To KIMANI MUTURI, the Founder and Director of TEXFAD Skills Training Academy, banana stems are the next big thing in Uganda’s entrepreneurship ecosystem. And it is not just a pipe dream. The Kyambogo University lecturer is living his passion by developing and commercialising innovations from the fibres in banana stems at his company’s headquarters in Mukono District. In this engaging interview, he discusses his company’s innovations like producing hair extensions from banana fibre, etc, as well as what the government of Uganda can do to support innovators.

Welcome to Menterprise Africa. We are joined by Mr. Kimani Muturi, the founder and director of TEXFAD Skills Training Academy. Could you share with us, for starters, what was behind the vision to start TEXFAD? How did you come up with an idea like this?

TEXFAD is a business that commercializes local innovations. And we strictly look at the resources that this country has; resources that are sustainable. And then we try to create innovations around those resources.

So, our focus has always been banana fibres and our concern is drawn from the many banana stems that go to waste in this country. And as you know, Uganda is one of the largest banana producing country in the world, and actually the largest in Africa. And we are also the largest banana consuming country in the world, meaning that that volume of bananas that we produce, we consume. So that comes along with a lot of waste in terms of [the] stems. And you can imagine even when you’re eating the yellow banana, just one banana like this, there is a stem somewhere flying and likely it is wasted.

So that became a concern and some years ago, I tried to think around how we can get some raw material from that waste, and we started research on how we can get the fibre out of the stem. Initially, it was quite hard. We started by extracting fibre by hand, get a piece of wood and then open up the stem, then lay the sheath on the stem and start scraping until you get the fibre. But it was not really for industrial purpose. So, when we founded the company in 2013, after proof of concept that we can extract banana fibres from the stem, then now we started developing a machine that could decorticate the fibre or extract the fibre from the stem, and we successfully did that. So, it helped us to manufacture quite a number of fibres, and then we started looking at the number of products that we could make. So, basically that is the motivation behind activities of extraction.

Yeah, that was quite innovative. And the idea that you even ended up producing your own machine to extract the fibre, how did that come about? Where was it done? Is it done locally or did you have to hire somebody from outside Uganda to do that?

Well, personally, I am not an engineer. I cannot design a machine, but I knew what I wanted, and, you know, Uganda has a very good non-formal industry that manufactures equipment in Katwe, Kalerwe. So, I created a partnership with one of the non-formal, or rather we call it juakali, sector. And then they came, they saw how I was extracting, and then we started now sharing ideas, and we started working on a prototype. So we worked on it until we were satisfied that what we have now can be able to support the company. And that’s how we made the machine.

Is this machine patented? Because it sounds like it’s your original development…

No. It is not patented.

And are you manufacturing it for others who want to get into the same business?

Yes, I am. We have around eight machines that are working for us with different farmers. Wherever they harvest, they extract, then they sell the fibre to TEXFAD. And we are also currently manufacturing, you’ve seen our workshop here, we are organizing that workshop and in the next one week, we should be manufacturing from TEXFAD because we’ve been doing it from outside. And the reason is we want to maintain our design local, we want to keep adjusting the machine according to the experiences that we go through as we extract and want to make the output of the machine or the capacity a little bit higher than it is now.

About patenting, I know it’s good to patent your original works, but when I go through the patented works and I see how the world is handling the patents, I feel I am at a loss by patenting an equipment, because you’ve seen how that machine is designed. If I patent it the way it is, somebody will just increase the measurement by maybe one millimetre, and that is different from my patent. Somebody can just change something very small, even the shape of the body or something, and then now you cannot claim that it is your technology because the measurements are not the same as yours. So that kind of competition, I think, is not healthy. It is rather good to let people access the technology, but have control of the equipment wherever it’s going, or the source for manufacturing, and then benefit by getting supplies of raw materials from these people.

You’ve talked about the abundance of the raw material for your innovation. How much of that material are you getting and how much is still out there that goes to waste?

If you look at the production of bananas in this country, let’s say Uganda produces 10 million metric tons of bananas…. TEXFAD has no capacity [to extract all the fibres from all those stems left behind after the bananas are cut down]. Our capacity is very, very low. It cannot even make one per cent, meaning that this is an industry that can grow big, and it’s an industry that can feed raw materials to a number of other industries that can use banana fibre for quite a number of things.

Have you received government support to try to grow this aspect of innovation?

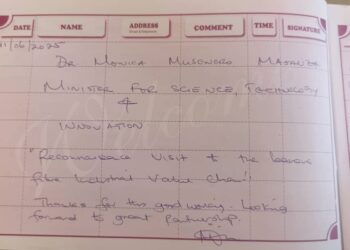

Well, the government is positive about what we are doing. We’ve had a number of fora with different government agencies about the banana fibre. We’ve had support from the National Council for Science and Technology to develop the hair extensions. And right now we are at the UNBS [Uganda National Bureau of Standards] level of certifying, and creating a standard for, banana fibre hair extensions. The Minister of Science and Technology was here just a few weeks ago, and we are in discussions with the ministry because the ministry has decided to focus now on banana fibre because they have focused on the fruit and you must have seen the BIRDC [Banana Industrial Research Development Centre], the organization that now adds value to the fruit. Now they’re focusing on TEXFAD to upscale what we are doing to be able to be significant in this banana fibre industry. So, I can say [the] government is positive about this, and they are coming in to support.

In terms of your capacity right now, what are you able to supply out there, say, on a weekly basis, on a monthly basis, on an annual basis, from. I am sure many people, for instance, are fascinated by the hair extensions. How much are you able to supply to the market at the moment?

We are still a cottage industry, and the challenge with these innovations is that you innovate something, but you don’t know even the equipment that can produce what you have just created. And those are some [of the] challenges that we get. So, we are still producing using domestic processes [and] cottage procedures, but we are looking forward to industrializing the process.

We have a softening equipment that is coming from Pakistan. It will be softening around 100 kilos of banana fibre per day. And it will be calibrated to a level that it can soften fibre for hair extensions and soften fibre for textiles. So, if that capacity can be reached to the optimum of a hundred kilos per day, then I can confidently say that in the very near future, a few months to come, maybe two or three, we’ll have the capacity to produce a hundred kilos of hair per day. But as per now our capacity could be like two kilos per day because of the procedures that we go through to make this extension.

You talked about the market for this product. This product now is becoming very famous because it seems the world is discovering that the synthetic hair has some chemical components that are not healthy to the body. And there’s research that is currently being done by the World Health Organization (WHO). We are actually waiting for their outcomes. But I have also followed quite a number of western media that is reporting that, the synthetic hair that is currently in use has some carcinogenic impact on black women. And, I don’t know, I’ve not accessed that study yet, but it has raised a lot of concern. And we are seeing a lot of calls from US, from UK in a week, we can get two new calls or three new calls. Some are asking for a ton of hair extension, two tons. There is somebody who was asking whether we can supply five tons every month. So, I see that this is an industry that is going to grow, but then the mechanization processes for what we are doing is what is lacking in order to meet the demand that we are beginning to see.

If you were to ask for outside help from the government, from organizations that support innovations in Africa, etc, what would that help be?

The support would be twofold. One is to create a manufacturing line. This manufacturing line would involve either buying equipment that is existing there or having an arrangement with manufacturers of different machinery like in China, like in India to manufacture a custom-made manufacturing plant for, let’s say, plant-based banana hair extensions. I think that support would help us so much.

The other support that we would go for… this hair also involves some softening procedures, and some of these procedures can either be chemical procedures for softening or organic enzymatic process. And since we are positioning ourselves as a manufacturer of sustainable products that cannot harm the environment, we would like to lean more towards organic procedures than chemical procedures. But then, there’s very little information about manufacturing of organic enzymes and support to have a laboratory that helps us to manufacture the enzymes, and also a lab that helps us to do some tests and measurements for quality assurance, the properties of our hair, and that kind of thing, would be very, very good.

Lastly, our banana fibre extractor machines are domestic, as I said, and their capacity is only 10 kilos per day, so you need so many small machines to reach even a hundred kilos per day. But out there, I know there are systems that decorticate like sisal and they can be customized to decorticate banana fibre, and we have tried with one and it worked very well. But now that is a heavy plant that can do like 200 kilos of fibres per day, and that is the [kind of] equipment that we would, maybe, go for should there be support extended to us.

You are clearly swimming in uncharted waters with regard to your innovation. What lessons have you picked from the 13 years of working in this space that others who may want to follow in your footsteps, not just with banana fibre, but with any other kind of innovations, can benefit from? What lessons have you picked that you can share with them?

One thing I can say is that it’s a passion. It’s passion. And when you’re investing in a passion, whatever you do makes you feel happy. Even losses, you don’t feel the losses that you make because it’s something that is within you, it’s an interest. And that is how it all begins. So, those who are now focusing on innovation must have the patience. After having the passion, they must have the patience to walk the journey. Because you can imagine you are extracting a banana tree, you want to get a fibre, you don’t know what that fibre can do. Maybe you have some scanty ideas, and you go ahead to invest in that. While your colleagues are investing in real estate, for you investing in something unknown. So, it becomes very difficult for many people to venture in what we are doing.

But we’ve been an inspiration to many, and I have a number of people now who got inspired from this place; a number of them are now making hair using their own procedures, even across Africa. We’ve conducted many trainings. We’ve done Mauritius two times, we’ve done Nigeria, we’ve done Cameroon, we’ve done Kenya recently and we are going to Ghana in the coming months. So, it is a technology that people are taking, but when they take, they begin to commercialize their own ideas within our ideas.

What message do you have for people who don’t know what you’re doing yet are potential customers who could make use of these products but are not yet aware? And what message do you have for the general public?

The message to them is that we are thinking ahead and we are also motivated by the number of youths that you find jobless in this country and in Africa in general. Now, when you look at those people out there, and when you look at what we are doing, they can pick a leaf from what we are doing, and they can replicate this from different materials, not necessarily banana fibre. They can do other materials. I see plants every day that can give you fibre, and I see so many resources on this land that can give you materials for making something. So, this can be an inspiration for those who want to start such businesses, to the youths who are out there who want to engage themselves in something.

To the potential customers, they have a good product that is Ugandan, that is a homegrown innovation that can be used to change their environment, to change their interior space, and we also give people a new feeling of interacting with natural materials that are homegrown.

I am trying to get in touch with Kiira Motos. I’ve already seen the managing director briefly, but we haven’t had a deep discussion. But my intention is to capture such people who are already in manufacturing, and they may have components that they may need in those cars that they’re making where banana fibre can be used either as a soundproof material, maybe as a particle board for maybe roofs of cars, the doors and all that so that we continue to customize even the materials that are used in manufacturing other products in this country. So, my call is, we have an abundance of this raw material, so how can the market out there utilize the raw materials or utilize the products that we are making, and all are invited?

If somebody wanted your products or if they wanted customized products, how do they reach you?

We are present on social media. We have an account with Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and we also have our website. And all these are channels where we do marketing, and we are very good at that. You also realize the kind of products that we are producing here are targeted for some class of people. So, we go to social media where we can find that class of, I call it a buying tribe, a tribe that buys our product.

We also have an outlet, a shop at Kira, at UN Mall, and that is where we have walk-in clients who come to buy our products. And that is where also customers come to deposit their orders and also collect the finished product because we don’t want to subject them to a long journey to the manufacturing cycle.

Based on your experience, what does the future hold for local innovation? And what would you want to see happening in the local innovation ecosystem in Uganda?

I would like [innovation] to be embraced in all sectors, and to those that I have had discussions with, I keep challenging them, because when you look around, people are more of consumers than producers. If you look at your home environment, there’s nothing likely that you have manufactured. The shoes you are wearing are made by someone. The shirt you’re wearing is made by someone. The saucepan you are using to cook, the soap, the matchbox, the shoe polish, you know, name it, someone is manufacturing. For how long are we going to be consumers? That is a question I always ask them.

And if you venture into that field of manufacturing, you find you may not outdo them, you may not do better, because they are already in the field and they are doing well. They are manufacturing and they are selling, and you are consuming. So, that is where the innovation comes in. If you are a tailor, for example, and your work is to make dresses, and you are also competing with the people who are making the same dresses, how can you bring innovation to your work so that your work becomes very unique? Now, this innovation can be in terms of the process, can be in terms of the material, and it can also be in terms of the product that you are going to make. For example, I have never seen someone manufacturing handkerchiefs in this country, and I think that could be the cheapest skill that somebody could get. I have never seen someone making undergarments like boxers and panties or even bras in this country. Now if you are a tailor, those are the areas where you can bring in your ideas and then you have an innovative product. You really don’t have to innovate something like you are just creating from scratch. You can get the existing and then you modify it and have a unique looking product, and it will help you hit the market.